What Do Twin Studies Tell Us About Genetics and the Ability to Read Emotions?

Abstruse

Human wellbeing is influenced by personality traits, in detail neuroticism and extraversion. Little is known about which facets that drive these associations, and the role of genes and environments. Our aim was to identify personality facets that are important for life satisfaction, and to judge the contribution of genetic and environmental factors in the association between personality and life satisfaction. Norwegian twins (N = 1,516, age 50–65, response rate 71%) responded to a personality musical instrument (NEO-PI-R) and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS). Regression analyses and biometric modeling were used to examine influences from personality traits and facets, and to estimate genetic and environmental contributions. Neuroticism and extraversion explained 24%, and personality facets deemed for 32% of the variance in life satisfaction. Four facets were particularly important; anxiety and low in the neuroticism domain, and activeness and positive emotions within extraversion. Heritability of life satisfaction was 0.31 (0.22–0.40), of which 65% was explained by personality-related genetic influences. The remaining genetic variance was unique to life satisfaction. The association between personality and life satisfaction is driven mainly by four, predominantly emotional, personality facets. Genetic factors play an of import role in these associations, but influence life satisfaction too across the effects of personality.

Introduction

Man wellbeing and life satisfaction are influenced past life events, health, economy and social relations1,2. Life satisfaction is besides closely connected to personality traits3,4, but the nature of this relation is partly unknown. At that place is express knowledge about which specific aspects, or facets, of personality are near important. Further, both personality and life satisfaction are influenced by genetic factors5,6,7,viii, but we have inadequate understanding of the role of genetic and environmental factors in explaining the links betwixt personality and life satisfaction. Which traits, and which particular facets, are virtually important for promoting or obstructing private life satisfaction? Are the associations accounted for by genetic factors, environmental factors, or both? Does the genetic influence on life satisfaction stalk entirely from personality related genetics, or do genetic factors for life satisfaction operate independently of personality?

The scientific study of the expert life and wellbeing has prospered in recent years9,10,eleven. Every bit the field has grown, a number of constructs and approaches have emerged. The construct of subjective wellbeing (SWB) occupies a central position, and is typically seen as comprising iii components - frequent positive touch, infrequent negative touch on, and presence of life satisfaction12. Life satisfaction represents a global evaluation of life, a mental summarizing of life as good, or non so skilful, according to the individual's own values, norms, and ideals13. As such, life satisfaction constitutes the key cognitive component in SWB and positive mental health12,14. In parallel with SWB, the construct of psychological wellbeing (PWB) contains components such equally engagement, personal growth, and flow-experiences, thereby focusing more on functioning well than feeling well15,16,17. Inquiry on SWB and PWB represent two unlike, but complimentary traditions, focusing on distinguishable notwithstanding related dimensions of wellbeing overall. The dimensions of SWB and PWB have likewise been integrated into broader models, such as the tripartite model of mental wellbeing (MWB) including emotional, psychological and also social wellbeingxviii. Thus, in correspondence with inquiry on taxonomies and the nature of psychopathology (i.e., illbeing), the wellbeing field today addresses several aspects of the good life. Life satisfaction represents a central component in SWB in detail, but features every bit an important attribute inherent in most models.

Genetics of Wellbeing

Genetic factors appear to play an important role in most human characteristics19 and wellbeing is no exception. Heritability estimates for dissimilar conceptualizations of wellbeing typically range from 0.30 to 0.5020,21,22,23,24,25. A meta-analysis of 13 studies from seven different countries and including more than 30,000 twins, reported a weighted average heritability of 0.40 for wellbeing5. This meta-analysis also found substantial heterogeneity in heritability estimates across studies, beyond that expected by random fluctuations, thus verifying the theoretical notion that there is no fixed heritability for wellbeing. Rather, the share of variance accounted for past genetic factors varies across cultures, historic period groups, and the particular wellbeing phenomena studied. Another meta-assay by Bartels6, with somewhat dissimilar inclusion criteria, samples and analytic strategy reported an average heritability of 0.36 for wellbeing.

There is evidence of a common genetic influence on different wellbeing components such every bit subjective happiness, life satisfaction, SWB and PWB24,26, only also genetic influences that are specific to the different components26,27. The genetic factors in wellbeing are partly related to the genetic influences on social back up28, and inversely, depression29 and internalizing disorders30,31,32. Additionally, longitudinal studies have shown that genetic factors business relationship for about of the stability in wellbeing with heritability for the stable variance, or dispositional wellbeing, estimated in the 70–ninety% range33,34. Past contrast, environmental factors constitute the major source of alter in wellbeing34,35.

Despite clear evidence of substantial genetic influences on wellbeing in general, findings on life satisfaction are somewhat divergent, with heritability estimates ranging from aught to 0.5924,32,35,36,37,38. The meta-analysis by Bartels6 examined heritability of life satisfaction specifically, and reported an boilerplate heritability of 0.32. Thus, life satisfaction appears to exist somewhat more than influenced by environmental factors than other dimensions of wellbeing. Further, although levels of life satisfaction normally vary only moderately with age, there might be age-related moderation of genetic and environmental factors. As life satisfaction represents an evaluation of life-so-far, life at older age likely include more life events, adversaries and accomplishments than life at younger age, thereby suggesting stronger environmental than genetic effects. At that place is a need for more than knowledge most the genetic and ecology influences on life satisfaction in the mature population, measured by validated and reliable multi-detail instruments.

Recent advances in molecular genetics have contributed to our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of wellbeing – including heritability. Genome-wide Complex Trait Assay (GCTA) uses genotyping of common Unmarried Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in unrelated individuals to approximate heritability. Rietveld, et al.39 reported that up to 18% of the variance in wellbeing can be explained by cumulative additive effects of genetic variants that are frequent in the population. This suggests that common genetic polymorphisms account for well-nigh half of the overall heritability of SWB. Genome-Wide Clan Studies (GWAS) are used to identify specific genetic variants associated with a phenotype. Recently, Okbay, et al.40 used GWAS in a sample of 298,420 individuals, and identified iii credible genetic loci associated with wellbeing. However, these three variants explained only a small fraction (4%) of the variance. Molecular genetic studies expand rapidly and are expected to provide of import new insights into the genetics of wellbeing. However, it also seems clear that twin and family unit studies are unique in their ability to capture the total genetic and ecology factors involved, along with the overall overlap and specificity beyond dissimilar characteristics.

Personality and Life-Satisfaction

Personality refers to relatively stable and feature patterns of noesis, emotion, and behavior that vary across individuals. These patterns are commonly described in terms of specific personality traits. The most widely known trait models today are the five-factor and big 5 models41,42, which converge on five broad personality traits, including extraversion, neuroticism, openness, conscientiousness, and conjuration. In that location is a well-established human relationship between personality traits and wellbeing in general, and personality and life satisfaction in particular3,4,43. More specifically, the big v traits of neuroticism and extraversion consistently explain substantial amounts of variance in wellbeing. The findings are more mixed regarding the trait of conscientiousness, whereas agreeableness and openness seem to play a limited, or negligible role in wellbeing3,43,44.

The five-cistron model of personality is hierarchical with the college-society domains (traits) comprising a fix of lower-lodge facets45. For example, in the NEO-PI perspective, equally developed by Costa and McCrae41, the domain of neuroticism includes the facets of anxiety, hostility, depression, cocky-consciousness, impulsiveness and vulnerability to stress. Correspondingly, the domain of extraversion includes warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement-seeking and positive emotions. Despite solid evidence for relations between the general big 5 factors and wellbeing, there is still express knowledge about which facets of the traits that contribute the well-nigh to wellbeing.

Theoretically, inter-personal facets such as warmth and gregariousness (sociability) contribute to wellbeing indirectly by creating well-functioning social relationships that subsequently influence wellbeing. Social back up and good social relations accept quite consistently been found to correlate positively with wellbeing28,46,47, and may partly be influenced past personality traits and facets.

There is also theoretical reason to expect factors contributing to accomplishments and goal attainment, in the conscientiousness domain, to be of import for life satisfaction48,49,fifty,51. Life satisfaction judgments consider the gap between bodily states and ideal states. Personality facets such as competence, self-discipline, achievement-striving and dutifulness may exist important in obtaining ideal states, and are thus likely to predict life satisfaction.

Finally, personality tendencies to sure emotional experiences, such as anxiety or positive emotions may similarly influence wellbeing every bit life satisfaction judgments are coloured past both electric current emotional states and by memories of past emotional episodes. For example, a personality disposition to feel positive emotions may contribute to many episodes of joy and enthusiasm. These episodes may constitute a footing for the subsequent evaluation of life and so far4,52,53. Thus, from a theoretical perspective both interpersonal facets, accomplishment-related facets and emotional facets would exist important in generating a expert life.

Empirical examinations of relations betwixt personality facets and life satisfaction are limited. Nevertheless, a few studies have shed light on the issue. Schimmack and colleagues52 found the low facet of neuroticism, and the positive emotions facet of extraversion to be the strongest and nigh consistent predictors of life satisfaction. They concluded that depression is more of import than anxiety or anger, and a cheerful temperament is more than of import than being active or sociable. Quevedo and Abella54 establish low and the achievement striving facet of conscientiousness, but not positive emotions, to be the important facets, whereas Albuquerque, et al.55 identified low and positive emotions equally central, and found an additional issue from the vulnerability facet of neuroticism. Finally, Anglim and Grant56 reported significant semi-partial correlations betwixt life satisfaction and the three facets of low, self-consciousness and cheerfulness.

These studies have provided of import knowledge about the nuanced associations between personality and life satisfaction, and bespeak to some particularly important personality facets. Notwithstanding, findings so far are limited, as the results are partly divergent, and mostly based on (young) student samples and convenience samples. Consequently, in that location is a need for replication of findings and expansion of cultures and age groups studied.

Genetic and Environmental Factors in Personality and Life Satisfaction

Personality traits are relatively stable characteristics, and there is considerable evidence for genetic components57,58. Although associations betwixt personality traits, and partly their facets, and wellbeing are established, at that place is limited cognition about the mechanisms involved in these associations. Are the associations between personality and wellbeing due to common genetic factors, and is the entire heritability of wellbeing deemed for past the genetic factors in personality – is wellbeing genetically speaking a personality thing?

A few studies have addressed these questions at the level of broad personality traits. First, Weiss and colleagues59 institute a global SWB-measure to be accounted for past unique genetic effects for neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness, and past a common genetic factor that influenced all 5 personality domains. Environmental factors also contributed to the associations, simply there were no genetic effects unique to SWB. In a like vein, Hahn and colleagues38 reported shared genetic furnishings for life satisfaction and the traits of neuroticism and extraversion, simply not conscientiousness. Both additive and non-additive genetic effects contributed to the relation between personality and life satisfaction, and once again the unabridged heritability of life satisfaction was accounted for by personality-related genetic factors. Finally, a study examining personality traits and flourishing found substantial genetic effects on the associations, but also identified a unique genetic influence on wellbeing, unrelated to personalitysixty. This latter study was unique in its focus on the construct of flourishing as comprising both eudaimonic and hedonic aspects of wellbeing, based on Keyes' tripartite model including emotional, psychological and social wellbeing61, and thereby also involving both feeling good and operation well.

Thus, a few recent studies have reported exciting show of a substantial genetic contribution to the clan betwixt personality traits and wellbeing. Yet, several important questions remain to be addressed. Outset, no studies to date have examined genetic and environmental contributions to the associations betwixt personality facets and wellbeing. Given the findings for broad personality traits, we hypothesize considerable genetic furnishings besides for their facets. Still, the magnitude of such furnishings is unknown. Second, simply i study38 has examined life satisfaction specifically – rather than global measures of wellbeing. Tertiary, as previous studies take relied just on short-course measures of broader traits, at that place is a pressing need for examining both traits and facets in relation to life satisfaction by ways of comprehensive, valid, well-established instruments. Quaternary, findings from the few previous studies are divergent every bit to whether the entire genetic effect on wellbeing is due to personality-related genetic influences. Fifth, whereas prior studies have examined samples with broad age ranges, nosotros wanted to examine a specific period in life – middle to belatedly adulthood – to assess how relatively stable personality characteristics contribute to life satisfaction in a life class perspective. Finally, as previous studies have been inconclusive regarding sexual practice-differences in the underlying etiology of wellbeing6,62, we also wanted to test for such differences.

The aims of the current study were to (a) identify personality traits and facets that contribute uniquely to life satisfaction, and thereby pinpoint the dispositional constituents of a happy personality, (b) approximate the heritability of life satisfaction in center to late adulthood, (c) disentangle the genetic and environmental influences shared by personality traits/facets, and life satisfaction, and finally hence to (d) determine whether all of the genetic influence on life satisfaction is due to personality related genetic factors as suggested by some previous studies.

Results

Correlation and Regression Analyses

As shown in Table 1, neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness were all significantly correlated with life satisfaction, while agreeableness and openness were not. The strongest correlation was establish for neuroticism, yet with substantial associations also for extraversion and conscientiousness. In the multiple regression assay including these three factors, merely neuroticism and extraversion showed significant unique contributions. The effects remained when controlling for sexual activity and age. A total of 24% of the variance in life satisfaction was accounted for.

We next examined the associations for all the thirty personality facets. Table two shows the resulting correlations. A total of 23 facets were significantly associated with life satisfaction. In the neuroticism domain, all facets showed significant correlations, ranging from −0.14 for impulsiveness to −0.51 for depression. Within extraversion, excitement seeking was well-nigh unrelated (0.05) to life satisfaction, whereas positive emotions (0.30) and activity (0.28) showed substantial associations. In the openness domain, only one facet, ideas, showed a significant but very pocket-size correlation (0.08). The conjuration domain was notable for a combination of positive and negative associations. Trust (0.17) and altruism (0.09) were positively associated with life satisfaction, while negative associations were shown for modesty (−0.08) and tendermindedness (−0.08). Finally, in the conscientiousness domain, all factors showed significant and positive correlations, and in particular competence (0.thirty) and cocky-subject field (0.28) appeared to be potentially important.

Next, regression analyses were conducted in which all 30 facets were tested simultaneously. Ten facets showed significant and unique effects (Table 2). In total, these facets explained 33% of the variance (adjusted Rii = 32%) in life satisfaction. Iv facets yielded substantial betas, that is in a higher place 0.10, and with p < 0.01, namely N1-feet, N3-depression, E4-activeness and E6-positive emotions (label N1 refers to Neuroticism facet 1, etc). The remaining meaning facets were found beyond all personality domains and included the openness facets of values and actions, the conjuration facet of compliance, and the conscientiousness facets of order and deliberation. Still, these effects were relatively minor (i.east., beta <0.x). Also, when performing Bonferroni correction and examining the False Discovery Rate63, merely the four facets with betas >0.ten retained p < 0.01. Thus, for the biometric analyses disentangling genetic and environmental effects nosotros focused on these iv facets with substantial and significant effects. Summarizing the regression findings, the happy, or satisfied personality is given by the equation:

$$\begin{array}{rcl}Happy\,personality & = & 0.12\,\ast \,Activity+0.xvi\,\ast \,Positive\,emotions\\ & & -0.fifteen\,\ast \,Anxiety-0.35\,\ast \,Low\terminate{assortment}$$

Biometric twin analyses

Twin-cotwin correlations beyond zygosity groups were calculated for the neuroticism and extraversion traits, the four major facets (i.e., anxiety, depression, positive emotion, activity) and life satisfaction. Table three shows the correlations. In general, the monozygotic (MZ) correlations were substantial, and in all cases higher than the corresponding dizygotic (DZ) correlations, indicating condiment genetic effects.

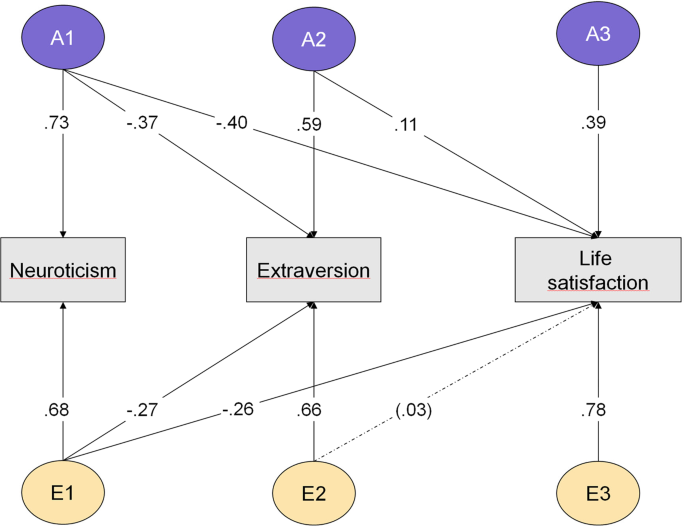

Based on the findings from the regression analyses, we next tested a set of tri-variate Cholesky models including neuroticism, extraversion and life satisfaction. Table 4 (upper part, block I) shows the fit of the different models. Model 1 included additive genetic (A), mutual ecology (C) and non-shared ecology (E) factors, and allowed estimates to vary across sex. Model ii, which included merely A and E effects, did not fit significantly worse (i.due east., Δ − 2LL = 0.89, Δdf = 12, north.s.) and produced a lower AIC value. Further, models 3 and 4, involving scalar sex-limitation, yielded additional improvements in fit, that is, increasingly lower AIC values, no meaning reduction in fit, and more than parsimony. Finally, models 5 and 6, where parameters were constrained to be equal across sex, resulted in higher AIC and worse fit. Thus, model 4 yielded overall best fit, and included only A and E effects with standardized parameters similar for men and women. Figure 1 shows the Cholesky parameters of the model.

Biometric Cholesky model of neuroticism, extraversion and life satisfaction. A = Additive genetic cistron; E = Not-shared environmental factor; All parameters: p < 0.05, except i parameter (n.s.) in parenthesis and dotted pointer.

Heritability estimates (with 95% CIs) were 0.53 (0.46; 0.60) for neuroticism, 0.49 (0.41; 0.56) for extraversion and 0.32 (0.23; 0.41) for life satisfaction. Based on the Cholesky model we too calculated the genetic and environmental correlations between the ii personality traits and life satisfaction. Genetic correlations were −0.70 (−0.58; −0.83) for neuroticism, and 0.53 (0.37; 0.68) for extraversion. Correspondingly, environmental correlations were −0.32 (−0.23; −0.40) for neuroticism and 0.15 (0.08; 0.24) for extraversion.

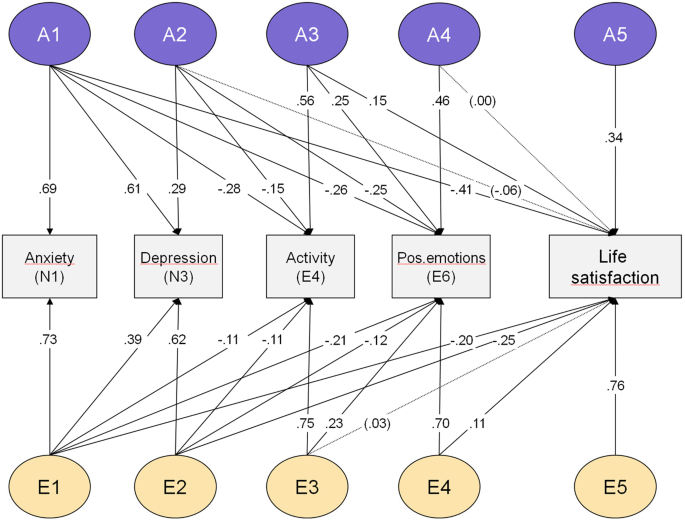

Moving from the big 5 factors to the personality facets, over again nosotros tested a set of models including the 4 facets found to be most strongly predictive of life satisfaction. Table 4 (lower part, block II, models 7–12) shows the results. Again, the best plumbing fixtures model included simply A and East furnishings (model ten), and standardized estimates did not differ beyond sex. Figure 2 shows the parameter estimates of the best model.

Biometric Cholesky model of four personality facets (anxiety, depression, activity and positive emotions) and life satisfaction. A = Additive genetic cistron; E = Not-shared environmental factor; N = Neuroticism; E = Extraversion. All parameters: p < 0.05, except iii parameters in parentheses and dotted arrows.

In this all-time-plumbing fixtures model, heritabilities were estimated to 0.47 (0.40–0.54) for feet, 0.46 (0.38–0.53) for depression, 0.42 (0.33–0.49) for activity, 0.40 (0.32–0.48) for positive emotions, and 0.31 (0.22–0.40) for life satisfaction. As tin can exist seen in Fig. two, genetic factors from both the neuroticism and extraversion facets uniquely influenced life satisfaction. However, after the effect of latent factor A1 (reflecting the genetic variance in anxiety) was deemed for, in that location was no boosted genetic issue from the unique genetic factor of low (A2). Besides, the genetic variance in activeness (A3) influenced life satisfaction, but there was no additional genetic upshot from positive emotions (E4). Thus, the genetic variance in each of the two personality domains, which influenced life satisfaction, appeared to be shared by the facets within their respective domain (neuroticism or extraversion), and the facet-specific influences on life satisfaction appeared to be driven by environmental effects. Notable is also the unique genetic factor (A5) influencing life satisfaction subsequently all the genetic effects of the facets were accounted for.

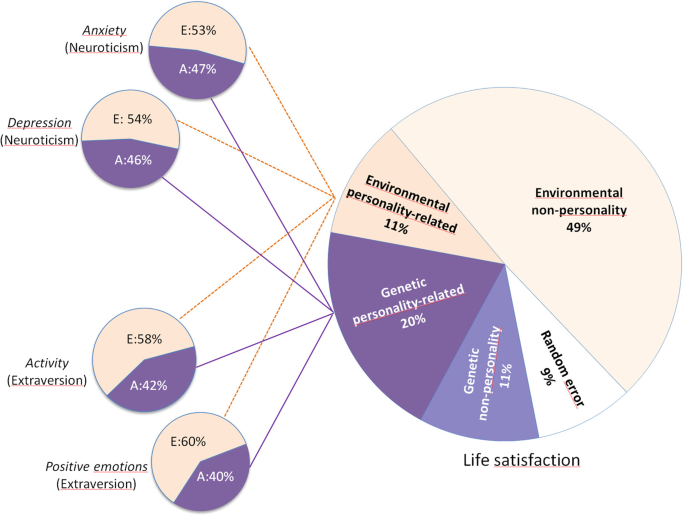

A full of 20% of the variance in life satisfaction was deemed for past personality-related genetic factors, and 11% was explained by a genetic factor unrelated to personality. Thus, of the total heritability of life satisfaction (h 2 = 0.31), about 65% was driven by personality genetic factors, and the remaining 35% was due genetic influences independent of personality. Further, the combined effect of personality facets on life satisfaction as well involved ecology furnishings, accounting for xi% of the variance. Finally, 58% of the variance in life satisfaction was ecology in origin and unrelated to personality. This environmental component includes random measurement error (one-blastoff = 9%), thus implying an estimated true not-shared environmental component of 49%. Effigy 3 shows the decomposed sources of variance for life satisfaction, along the corresponding variance components of the iv facets.

Life satisfaction: Sources of origin decomposed. Genetic and not-shared environmental components, divided into personality-based and non-personality sources. Estimated random error (1-α) also shown for life satisfaction. For facets, condiment genetic (A) and non-shared environmental variance (E) shown.

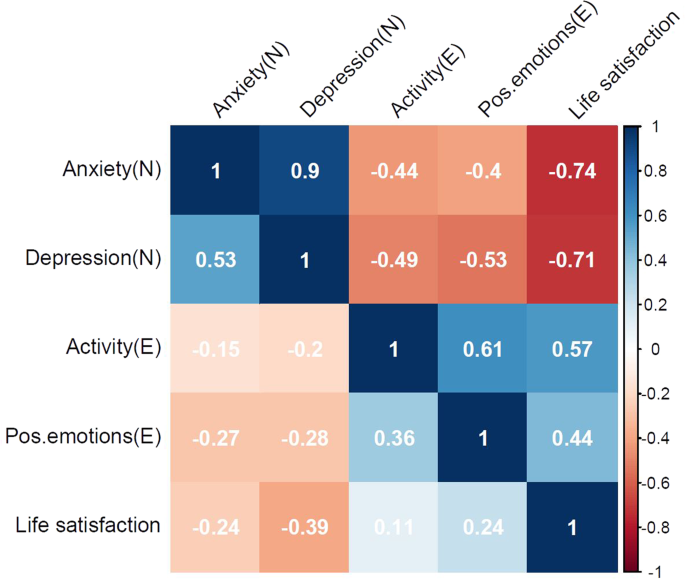

Based on the best-plumbing fixtures model, we besides calculated genetic and environmental correlations for the variables, shown in Fig. 4, above and below the diagonal, respectively. Generally, the genetic correlations inside personality domains were high, and the genetic correlations between facets and life satisfaction were moderate to loftier. The corresponding environmental correlations were generally lower, but suggested also of import associations due to environmental factors.

Genetic and ecology correlations, above and below diagonal, respectively.

Discussion

We set out to delineate etiological factors involved in the associations between personality and life satisfaction. Personality traits are well-established predictors of wellbeing in general and life satisfaction in detail3,43. The issue of why personality traits influence life satisfaction was addressed along 2 paths: Outset, we examined the broad personality traits and the specific personality facets that drive the effects from traits. Second, we examined the role of genetic and environmental factors in the link between personality and life satisfaction.

Personality and life satisfaction

At the level of broad traits, neuroticism and extraversion were uniquely predictive of life satisfaction, in line with previous studies3,4. Farther, iv facets of unique importance for life satisfaction were identified, namely anxiety and depression from the neuroticism domain, and positive emotions and activity from the extraversion domain. The happy, or satisfied personality thus seems to accept low levels of feet and low, and high levels of positive emotions and activeness. The highly emotional nature of these facets is noteworthy. That is, three out of the four facets explicitly refer to affective tendencies, whereas the fourth facet (activity) adds vigor, energy and liveliness41. Thus, the cognitive evaluation of life satisfaction is partly based on emotional tendencies inherent in the big five model. Our findings accordance with previous studies in identifying depression, and partly positive emotions, as fundamental predictors of life satisfaction52,55. Withal, whereas prior studies have found facets such as vulnerability, excitement-seeking52, and achievement striving54 to be significant, in this population based sample covering heart to late machismo, we establish anxiety and activeness to exist important.

Although a high number of facets were correlated with life satisfaction at the zippo-gild level, most facets did non show unique effects on life satisfaction in the multivariate analyses. There were no unique effects from interpersonal facets such equally warmth, assertiveness, gregariousness, trust or straightforwardness. Neither did we observe effects from accomplishment-related facets such equally competence, self-subject field or dutifulness. This does not imply that having warm and trustful relations, or high levels of competence, are inconsequential for wellbeing. Rather, we interpret the findings to suggest that the predominantly emotional facets are underlying tendencies accounting for some of the zero-society associations betwixt other facets and life satisfaction.

Why and how do depression, anxiety, positive emotions and activity play such important roles in generating a good – or not so good – life? We believe that a dual set of mechanisms are involved. First, from a height-down perspective64,65, life satisfaction is influenced by a general fashion of seeing life, the glasses through which we perceive the earth. Therefore, negative and positive affective tendencies might color our ongoing evaluations of what life has been similar.

Second, and in accordance with a bottom-upwardly perspective64, positive and negative affective tendencies over time contribute to life experiences that are taken into business relationship when performing a current evaluation. That is, a person with a strong tendency to experience positive emotions and action/energy, combined with a low tendency to low and anxiety, might recall a high number of episodes characterized by such experiences, and thereby summarize life as mostly skillful. In contrast, a person prone to anxiety and depression, who experiences few positive emotions and low action/energy, might have a mental album comprising of numerous episodes and life periods that are less satisfactory.

Importantly, low (sadness/distress), feet (fright) and positive emotions are represented in almost models of basic emotions66,67,68,69. These bones emotions are seen equally evolutionary adaptive and functional responses to environmental exposures. Although we are all equipped with the potential to feel such emotions, from a personality perspective there are individual differences in our tendency to activate them, and as such they are encompassed as facets in the 5-factor personality model. Adding the facet of activity (energy) to the equation we have four basic building blocks, inherent in our personality, that contribute uniquely to a practiced life. In a dual-process model these tendencies operate both past coloring current perceptions of life-so-far, and past having contributed to a number of positive and/or negative experiences throughout the life lived.

In the wellbeing-illbeing structural model (WISM), wellbeing is conceptualized as comprising both well-staying and well-moving, and illbeing is correspondingly divided into ill-staying and ill-movingxv,23. The model posits that humans have various goal states, and nosotros may experience the presence of an obtained goal country (well-staying), nosotros may be in a procedure towards a desired goal (well-moving), we may feel threats implying a adventure of losing goals (ill-moving), and finally we may realize that a goal state is lost (ill-staying). The current findings are noteworthy in identifying personality facets that take certain connections to these four goal-state conditions. Positive emotions can exist seen as indicative of well-staying, action is potentially important for well-moving, anxiety is a core feature of sick-moving and depression is a characteristic of loss and ill-staying. Thus, our findings lend support to the notion of well-staying, well-moving, sick-staying and ill-moving as central human being scenarios that all are important for generating or obstructing good lives.

The role of genetic and environmental factors

The estimated heritability for life satisfaction was 0.31. This is in the lower range of previous estimates for general wellbeing24,35, and below a meta-analysis estimate of 0.405. However, although findings are divergent, several studies have reported heritability estimates for life satisfaction that are moderately lower than for other wellbeing constructs32,seventy,71, and the meta-analysis by Bartelshalf-dozen reported a heritability of 0.32 for life satisfaction. Our written report is one of the first to examine life satisfaction across midlife specifically, with a well-established instrument. The findings point to both genetic and environmental influences – however with the latter clearly being the most important. As such, life satisfaction appears to be more almost the environmentally influenced life form, events and relationships, than well-nigh a genetically driven trend. Such an interpretation also implies potentials for change in life satisfaction, and peradventure substantial benefits of wellbeing interventions35,72.

We tested models examining sex-differences in the genetic and environmental sources of wellbeing. In line with several studies6,21,seventy, but in contrast to some others62,73, nosotros constitute the heritability, and the ecology component, to be of similar magnitude for females and males. Although the total variance might vary, our findings provide evidence that the relative contribution of genetic factors is similar across sex.

While genetic factors seem to play only a moderate role for the total variability in life satisfaction, genetic factors announced to take a major office in the association betwixt personality and life satisfaction. Both at the levels of broad traits and more specific facets, genetic factors were highly important in explaining the effect of personality on life satisfaction. That is, at that place are genetic factors influencing personality that likewise influence life satisfaction, whereas environmental factors play a more express role in this human relationship. More specifically, the genetic dispositions to experience a low caste of depression and anxiety, and a high degree of positive emotions and activity contribute to a life experienced as good and satisfactory.

To our cognition this study is the very get-go to examine genetic factors in the association between personality facets and life satisfaction. In full general, our finding of genetic factors playing a key office accord with the few previous studies examining wide personality traits and wellbeing in genetically informative samples38,59,74. All the same, whereas two of these previous studies plant the entire heritability of wellbeing to exist due to personality-related genetic factors38,59, in line with Keyes et al.60 we identified a unique genetic gene influencing life satisfaction beyond the effect of personality, accounting for xi% of the full variance. We tin can only speculate on the genetic mechanisms involved. Theoretically, there could be a specific, genetically driven, tendency to having a positive outlook on life that is not captured within the five-gene model. Alternatively, there could be influences from conditions such equally mental abilities or somatic disorders – both of which have substantial genetic influences19 – that too are outside the personality domain. Further studies are required both to address this aspect of life satisfaction, and by and large to delineate the complex processes starting with DNA-molecules and ending upwards with a person evaluating her life every bit good – or not.

The findings also accord with a recent molecular genetic written report of the association between wellbeing and neuroticism. Okbay, et al.forty used GWAS and bivariate Linkage Disequilibrium Score regression, and reported a genetic correlation of −0.75 between wellbeing and neuroticism. Despite the limited variance explained in the GWAS it is noteworthy that the correlation corresponds highly with the current estimate of genetic correlations of −0.lxx for neuroticism, −0.74 for the anxiety facet, and −0.71 for the low facet.

It is also noteworthy that in that location was a common genetic factor for feet and low that contributed to life satisfaction, and there was no unique genetic variance in depression that predicted life satisfaction beyond that shared with anxiety. The facet-specific influences appear to be driven past environmental furnishings. Corresponding findings were seen for extraversion; a common genetic cistron for activity and positive emotions contributed to the genetic variance in life satisfaction.

Strengths of the electric current study include a population based sample, a fairly high response charge per unit, and well-established extensive measurements. Nonetheless, some limitations should be noted. First, as with whatever twin study, heritabilities and genetic correlations are not fixed figures, but are estimated for a sure population, and simply future studies can validate the findings across other societies and age groups. Second, the sample size implies express ability to identify pocket-size effects – potentially common environmental factors or sexual practice differences. Third, although the NEO-PI-R is a well-established instrument, the reliabilities of the facets were partly express. Measurement error is captured in the E-factor in the biometric analyses, and might contribute to reduced environmental, but not genetic, correlations.

Conclusion

The findings replicate previous studies of wellbeing and life satisfaction equally influenced by genetic factors – with heritabilities in the 30–xl% rangefive,6. We likewise replicate substantial associations between wellbeing and personality, both for the full general traits of neuroticism and extraversion, and for specific facets3,52,56. Moreover, we identified four personality facets that appear to play an important role in driving the associations betwixt personality and life satisfaction. These facets include basic emotional tendencies, and point to the importance of emotions as sources of direct and indirect pathways that contribute to good lives. Roughly 2 thirds of the genetic variance in life satisfaction was plant to exist due to these facets. In add-on, we establish a sure genetic component in life satisfaction unrelated to personality traits or facets. Finally, the findings provide solid evidence of the role of ecology factors in generating good lives – also by contributing to associations between personality and life satisfaction.

Methods

Sample

Twins were recruited from the Norwegian Twin Registry (NTR). The registry comprises several cohorts of twins75,76, and the current written report drew a random sample from the cohort built-in 1945–1960. In 2010, questionnaires were sent to a total of 2,136 twins. Afterward reminders, 1,516 twins responded, yielding a response rate of 71%. Of the participants, ane,272 individuals were pair responders, and 244 were single responders. Zygosity has previously been determined based on questionnaire items shown to classify correctly 97–98% of the twins77. The cohort, every bit registered in the NTR, consists just of same-sex twins, and the study sample consisted of 290 monozygotic (MZ) male twins, 247 dizygotic (DZ) male person twins, 456 MZ female twins and 523 DZ female twins. The age range of the sample was l–65 years (mean = 57.eleven, sd = iv.five). The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Enquiry Ideals of South-Eastward Kingdom of norway, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

Life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) developed by Ed Diener and colleagues78,79. The SWLS contains five items, such equally "I am satisfied with my life". Response options range from 1 =strongly disagree to seven =strongly agree. The SWLS is widely used in wellbeing inquiry, and has well-established psychometric properties80. Cronbach's alpha in the current sample was 0.91.

Personality was measured by the NEO-PI-R45,81. The NEO-PI-R contains 240 items tapping the 5 general factors of personality, namely neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Within each of these factors, or domains, the NEO-PI-R measures vi facets, or sub-factors (see results section for overview of all 30 facets). Each of these facets is measured by 8 items. Response options range from 1 =strongly disagree to 5 =strongly hold. The NEO-PI-R is a well-established musical instrument, with sound psychometric properties41. In the current sample alphas for the 5 factors were 0.92 (neuroticism), 0.87 (extraversion), 0.88 (openness), 0.84 (agreeableness) and 0.87 (conscientiousness). Alphas for the facets ranged from 0.47 (C5 cocky-field of study) to 0.85 (N1 anxiety), with a mean of 0.67.

Analyses

Correlations were used to examine the bivariate associations between life satisfaction and personality traits and their facets. Adjacent, we used regression analyses to (a) examine the unique contributions from the five broad personality traits, and to (b) identify the facets that are of import for the association betwixt personality and life satisfaction. Due to the non-independence of observations inside twin pairs nosotros used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to account for the paired construction to obtain correct standard errors and significance levels. Further, to adjust for multiple testing nosotros performed subsequent analyses with Bonferroni correction and the False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach63.

Based on the regression analyses we conducted two sets of multivariate biometric analyses to estimate the genetic and environmental contributions to the associations between personality and life satisfaction. The first set examined the relation betwixt the major big 5 factors and life satisfaction. The 2nd prepare of analyses focused on the specific facets that uniquely predicted life satisfaction. In order to focus on facets with noun effects, we chose to retain simply facets yielding regression betas >0.10, and with p < 0.01.

Standard Cholesky models82,83 were used to estimate the genetic and environmental contributions to variance and covariance in personality and life satisfaction. All models were run with the OpenMx packet in R84. The biometric models take advantage of the basic premise that MZ twins share 100% of their genes, whereas DZ twins share on average 50% of their segregating genes. By and large, the models allow for estimating three major sources of variance, including additive genetic factors (A), common environment (C) and non-shared environment (Eastward). In addition, non-condiment genetic effects (D) may be tested, but are merely indicated if the observed MZ-correlations are more than than twice the DZ-correlations. A Cholesky model is a structural equation model comprising the measured variables as observed phenotypes and the A, C and E components equally latent factors (for illustration run across Fig. 1). Models are constrained so that latent A-factors correlate perfectly among MZ-twins, and at 0.5 among DZ-twins. C-factors are correlated at unity for both zygosity groups, and E-factors are by definition uncorrelated. Unlike models are compared to determine the presence of the genetic and environmental effects (e.m., the fit of an ACE model is compared to an AE model) or sex activity-differences. In line with standard practice, we tested dissimilar types of sex-limitation models85. Commencement, common sex-limitation models allow parameter estimates to vary beyond sex, involving differences in magnitude for genetic and ecology effects. 2nd, scalar sex activity-limitation allows the unstandardized variance-covariance matrices to vary across sexual practice, but standardized parameters (e.g., heritabilities) are constrained to exist equal. Finally, the sex-limitation models were compared with models having all parameters constrained to equal beyond sex. To appraise models and identify the best plumbing fixtures model we used the minus2LogLikelihood difference (Δ − 2LL) test, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)86.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the electric current written report may be requested from the Norwegian Twin Registry. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used nether license for the electric current written report, and and then are not publicly available. Information about data access is available here: https://www.fhi.no/en/studies/norwegian-twin-registry/

References

-

Diener, E., Oishi, Southward. & Tay, 50. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Man Behaviour (2018).

-

Jebb, A. T., Tay, Fifty., Diener, E. & Oishi, Southward. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the globe. Nature Human Behaviour two, 33–38 (2018).

-

DeNeve, Grand. M. & Cooper, H. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 124, 197–229 (1998).

-

Lucas, R. East. & Diener, E. In Handbook of personality: Theory and inquiry (tertiary ed.) (eds John, O. P., Robins, R. West. & Pervin, L. A.) 795–814 (Guilford Press; Us, 2008).

-

Nes, R. B. & Røysamb, E. In Genetics of Psychological Well-Beingness (ed. Pluess, K.) 75–96 (Oxford University Press, 2015).

-

Bartels, M. Genetics of wellbeing and its components satisfaction with life, happiness, and quality of life: A review and meta-analysis of heritability studies. Behavior Genetics 45, 137–156 (2015).

-

Johnson, W. & Krueger, R. F. Genetic and environmental structure of adjectives describing the domains of the Big Five Model of personality: A nationwide US twin study. J Res Pers 38, 448–472 (2004).

-

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J. & Vernon, P. A. Heritability of the big five personality dimensions and their facets: A twin written report. Journal of Personality 64, 577–591 (1996).

-

Lucas, R. East. & Diener, E. In Handbook of emotions (third ed.) (eds Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J. K. & Barrett, L. F.) 471–484 (Guilford Printing; US, 2008).

-

Diener, East. et al. Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on Subjective Well-Being. Can Psychol 58, 87–104 (2017).

-

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. Handbook of well-being. (DEF Publishers, 2018).

-

Diener, E., Oishi, Due south. & Lucas, R. Due east. In Oxford handbook of positive psychology (second ed.) 187–194 (Oxford Academy Press; US, 2009).

-

Kahneman, D., Diener, E. & Schwarz, Due north. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. 1999. xii, 593 (Russell Sage Foundation; US, 1999).

-

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E. & Smith, H. L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin 125, 276–302 (1999).

-

Røysamb, E. & Nes, R. In Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-being (ed. Vitterso, J.) (Springer, 2016).

-

Ryff, C. D. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom 83, 10–28 (2014).

-

Huta, V. & Waterman, A. S. Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a Classification and Terminology for Understanding Conceptual and Operational Definitions. J Happiness Stud 15, 1425–1456 (2014).

-

Keyes, C. L. Grand., Myers, J. M. & Kendler, K. South. The structure of the genetic and environmental influences on mental well-being. Am. J. Public Health 100, 2379–2384 (2010).

-

Polderman, T. J. C. et al. Meta-assay of the heritability of man traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nature Genet. 47, 702–709 (2015).

-

Nes, R. B. Happiness in behaviour genetics: Findings and implications. J Happiness Stud 11, 369–381 (2010).

-

Røysamb, Due east., Tambs, G., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Neale, Chiliad. C. & Harris, J. R. Happiness and wellness: Environmental and genetic contributions to the human relationship between subjective well-existence, perceived wellness, and somatic illness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85, 1136–1146 (2003).

-

Nes, R. B. & Røysamb, Due east. Happiness in behaviour genetics: An update on heritability and changeability. J Happiness Stud eighteen, 1533–1552 (2016).

-

Røysamb, Due east. & Nes, R. B. In Handbook of well-being (eds Diener, Due east., Oishi, S. & Tay, L.) Ch. The genetics of well-existence (DEF Publishers, 2018).

-

Bartels, Grand. & Boomsma, D. I. Built-in to be happy? The etiology of subjective well-being. Behavior Genetics 39, 605–615 (2009).

-

Archontaki, D., Lewis, G. J. & Bates, T. C. Genetic influences on psychological well-existence: a nationally representative twin report. Journal of Personality 81, 221–230 (2013).

-

Franz, C. Eastward. et al. Genetic and environmental multidimensionality of well- and ill-existence in middle aged twin men. Behavior Genetics. 42, pp (2012).

-

Archontaki, D., Lewis, G. J. & Bates, T. C. Genetic influences on psychological well-beingness: A nationally representative twin study. Journal of Personalit y. 81, pp (2013).

-

Wang, R. A. H., Davis, O. S. P., Wootton, R. E., Mottershaw, A. & Haworth, C. M. A. Social support and mental health in belatedly boyhood are correlated for genetic, besides every bit environmental, reasons. Sci Rep-Uk 7 (2017).

-

Nes, R. B. et al. Major depression and life satisfaction: A population-based twin study. J Touch Disorders 144, 51–58 (2013).

-

Kendler, Grand. Due south., Myers, J. G., Maes, H. H. & Keyes, C. L. M. The relationship between the genetic and environmental influences on common internalizing psychiatric disorders and mental well-existence. Beliefs Genetic south. 41, pp (2011).

-

Bartels, M., Cacioppo, J. T., van Beijsterveldt, T. C. E. Chiliad. & Boomsma, D. I. Exploring the association betwixt well-beingness and psychopathology in adolescents. Behavior Genetic s. 43, pp (2013).

-

Nes, R. B., Czajkowski, Northward., Røysamb, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. & Tambs, K. Well-being and ill-being: Shared environments, shared genes? The Journal of Positive Psychology 3, 253–265 (2008).

-

Nes, R. B. & Røysamb, Due east. Happiness in Behaviour Genetics: An Update on Heritability and Changeability. J Happiness Stud xviii, 1533–1552 (2017).

-

Nes, R. B., Røysamb, E., Tambs, K., Harris, J. R. & Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. Subjective well-being: genetic and environmental contributions to stability and alter. Psychological Medicine 36, 1033–1042 (2006).

-

Røysamb, E., Nes, R. B. & Vitterso, J. In Stability of Happiness (eds Sheldon, K. & Lucas, R. E.) (Elsevier, 2014).

-

Caprara, Chiliad. 5. et al. Human being Optimal Performance: The Genetics of Positive Orientation Towards Cocky, Life, and the Future. Behavior Genetics 39, 277–284 (2009).

-

Harris, J. R., Pedersen, North. L., Stacey, C., McClearn, M. & Nesselroade, J. R. Age differences in the etiology of the relationship between life satisfaction and self-rated wellness. Journal of Aging and Health 4, 349–368 (1992).

-

Hahn, East., Johnson, W. & Spinath, F. Yard. Across the heritability of life satisfaction-The roles of personality and twin-specific influences. J Res Pers 47, 757–767 (2013).

-

Rietveld, C. A. et al. Molecular genetics and subjective well-being. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.s. 110, 9692–9697 (2013).

-

Okbay, A. et al. Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nature Genet. 48, 624–633 (2016).

-

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. NEO PI-R. Professional Transmission. (Psychological Assessment Resourses, 1992).

-

Goldberg, Fifty. R. An Culling Description of Personality - the Large-5 Gene Structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59, 1216–1229 (1990).

-

Steel, P., Schmidt, J. & Shultz, J. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 134, 138–161 (2008).

-

Vitterso, J. Personality traits and subjective well-being: Emotional stability, non extraversion, is probably the important predictor. Personality and Individual Difference southward. 3ane, pp (2001).

-

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Domains and Facets - Hierarchical personality-assessment using the revised NEO personality-inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment 64, 21–50 (1995).

-

Bergeman, C., Plomin, R., Pedersen, North. 50. & McClearn, 1000. Genetic mediation of the relationship between social support and psychological well-being. Psychol Aging 6, 640–646 (1991).

-

David, South. A., Boniwell, I. & Conley Ayers, A. The Oxford handbook of happiness. 1097 (Oxford Academy Press; US, 2013).

-

Seligman, M. E. P. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-beingness. xii, 349 (Complimentary Press; US, 2011).

-

Headey, B. Life goals matter to happiness: A revision of set-point theory. Soc Indic Re s. 8vi, pp (2008).

-

Oishi, South. & Diener, E. Goals, culture, and subjective well-being. Pers Soc Psychol B 27, 1674–1682 (2001).

-

Sheldon, K. M. et al. Persistent pursuit of need-satisfying goals leads to increased happiness: A 6-month experimental longitudinal study. Motiv Emotion 34, 39–48 (2010).

-

Schimmack, U., Oishi, S., Furr, R. G. & Funder, D. C. Personality and life satisfaction: A facet-level analysis. Pers Soc Psychol B 30, 1062–1075 (2004).

-

Schimmack, U., Diener, East. & Oishi, S. Life-satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: The use of chronically accessible and stable sources. Journal of Personality seventy, 345–384 (2002).

-

Quevedo, R. J. M. & Abella, M. C. Well-being and personality: Facet-level analyses. Personality and Private Differences l, 206–211 (2011).

-

Albuquerque, I., de Lima, M. P., Matos, Chiliad. & Figueiredo, C. Personality and Subjective Well-Being: What Hides Behind Global Analyses? Soc Indic Res 105, 447–460 (2012).

-

Anglim, J. & Grant, S. Predicting Psychological and Subjective Well-Being from Personality: Incremental Prediction from 30 Facets Over the Large 5. J Happiness Stud 17, 59–fourscore (2016).

-

Bouchard, T. J. Genetic influence on human psychological traits - A survey. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13, 148–151 (2004).

-

Jang, K. Fifty., McCrae, R. R., Angleitner, A., Riemann, R. & Livesley, Westward. J. Heritability of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: Support for a hierarchical model of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74, 1556–1565 (1998).

-

Weiss, A., Bates, T. C. & Luciano, M. Happiness is a personal(ity) thing: The genetics of personality and well-being in a representative sample. Psychological Scientific discipline xix, 205–210 (2008).

-

Keyes, C. L. Chiliad., Kendler, Chiliad. Southward., Myers, J. M. & Martin, C. C. The Genetic Overlap and Distinctiveness of Flourishing and the Big V Personality Traits. J Happiness Stud 16, 655–668 (2015).

-

Keyes, C. L. M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J Wellness Soc Behav 43, 207–222 (2002).

-

Røysamb, E., Harris, J. R., Magnus, P., Vitterso, J. & Tambs, K. Subjective well-being. Sex-specific furnishings of genetic and environmental factors. Personality and Private Differences 32, 211–223 (2002).

-

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Decision-making the False Discovery Rate - a Applied and Powerful Arroyo to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met 57, 289–300 (1995).

-

Feist, Chiliad. J., Bodner, T. E., Jacobs, J. F. & Miles, Grand. & Tan, V. Integrating Summit-down and Bottom-upwards Structural Models of Subjective Well-Existence - a Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68, 138–150 (1995).

-

Marsh, H. Westward. & Yeung, A. South. Height-downward, lesser-up, and horizontal models: The direction of causality in multidimensional, hierarchical self-concept models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75, 509–527 (1998).

-

Ekman, P. Facial Expressions of Emotion - New Findings, New Questions. Psychological Science 3, 34–38 (1992).

-

Ekman, P., Sorenson, E. R. & Friesen, Due west. V. Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion. Science 164, 86–& (1969).

-

Izard, C. Due east. Basic Emotions, Natural Kinds, Emotion Schemas, and a New Epitome. Perspect Psychol Sci 2, 260–280 (2007).

-

Izard, C. E. Emotion Theory and Research: Highlights, Unanswered Questions, and Emerging Issues. Annu Rev Psychol 60, 1–25 (2009).

-

De Neve, J.-Due east., Christakis, Northward. A., Fowler, J. H. & Frey, B. S. Genes, economics, and happiness. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 5, 193–211 (2012).

-

Franz, C. E. et al. Genetic and environmental multidimensionality of well- and sick-being in middle aged twin men. Behavior Genetics 42, 579–591 (2012).

-

Bolier, L. et al. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Bmc Public Wellness 13 (2013).

-

Bartels, Chiliad., Cacioppo, J. T., van Beijsterveldt, T. C. & Boomsma, D. I. Exploring the association between well-existence and psychopathology in adolescents. Behavior Genetics 43, 177–190 (2013).

-

Keyes, C. Fifty. M., Kendler, K. South., Myers, J. Thou. & Martin, C. C. The Genetic Overlap and Distinctiveness of Flourishing and the Big Five Personality Traits. J Happiness Stud xvi, 655–668 (2014).

-

Nilsen, T. Due south. et al. The Norwegian Twin Registry from a Public Health Perspective: A Research Update. Twin Res Hum Genet 16, 285–295 (2013).

-

Harris, J. R., Magnus, P. & Tambs, Thou. The Norwegian Establish of Public Health twin plan of research: An update. Twin Res Hum Genet nine, 858–864 (2006).

-

Magnus, P., Berg, K. & Nance, W. E. Predicting Zygosity in Norwegian Twin Pairs Built-in 1915–1960. Clin Genet 24, 103–112 (1983).

-

Diener, East., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49, 71–75 (1985).

-

Pavot, Westward. & Diener, E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psycholog y. iii, pp (2008).

-

Pavot, W. & Diener, Eastward. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Calibration. Psychological Cess 5, 164–172 (1993).

-

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Stability and change in personality assessment: The Revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. Journal of Personality Assessment 68, 86–94 (1997).

-

Loehlin, J. C. The Cholesky arroyo: A cautionary note. Behavior Genetics 26, 65–69 (1996).

-

Neale, M. C. & Cardon, Fifty. R. Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. (Kluwer Bookish; 1992., 1992).

-

Boker, Southward. et al. OpenMx: An Open Source Extended Structural Equation Modeling Framework. Psychometrika 76, 306–317 (2011).

-

Neale, M. C., Røysamb, E. & Jacobson, K. Multivariate genetic assay of sex limitation and G x E interaction. Twin Res Hum Genet ix, 481–489 (2006).

-

Akaike, H. Factor-Analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 52, 317–332 (1987).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Eastward.R.: Data collection, analyses, conceptual model, writing of chief manuscript text. R.B.Northward.: Data interpretation, theoretical perspective, critical revision of text. Northward.O.C.: Analyses, critical revision of text. O.V.: Data collection, blueprint, critical revision of text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's notation: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the article'due south Artistic Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If textile is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will demand to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this article

Røysamb, E., Nes, R.B., Czajkowski, N.O. et al. Genetics, personality and wellbeing. A twin study of traits, facets and life satisfaction. Sci Rep viii, 12298 (2018). https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41598-018-29881-10

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29881-10

Further reading

Comments

By submitting a comment you concord to abide past our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines delight flag it equally inappropriate.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-29881-x

0 Response to "What Do Twin Studies Tell Us About Genetics and the Ability to Read Emotions?"

Postar um comentário